A new AI video installation dramatizes the technology’s potential to influence memory, desire, and the perception of history

What makes a memory? And how might that memory affect what it is possible for an individual to think, to feel, and to see—subtly guiding the choices and actions that determine the course of our shared future?

These are some of the questions that might flicker through the mind of a visitor to The Pilgrimage, an AI video installation within the group exhibition “Time Space Existence,” presented by the European Cultural Centre during the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale (May 20—November 26). Produced with the support of a 2022-23 Mellon Faculty Grant from the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST), the project is part of the wider concept of Bootleg Futures developed by Ana Miljački, associate professor of architecture at MIT and director of the Critical Broadcasting Lab (CBL).

Taking the form of a triptych of AI-generated videos of postwar monuments in the former territories of Yugoslavia, The Pilgrimage is an unusually personal project for Miljački. The daughter of two architects, she spent her childhood in Belgrade and left Yugoslavia shortly before the country’s dissolution in 1991.

As a critic, curator, and educator, Miljački’s work has focused on the role of architecture in Cold War era Eastern Europe, informing her wider interest in mechanisms of communication and conditioning in the built environment. Her work with CBL involves critical interventions into architectural thinking and practice through provocative and playful interpretations of broadcasting media, often using archival material as a starting point for creativity. In the case of The Pilgrimage, the prima materia is Miljački’s own memory.

Histories of Influence

“My classmates and I would visit these monuments, on trips organized by our elementary schools or the League of Socialist Youth of Yugoslavia,” explained Miljački. “We would leave in buses from school, each with a packed lunch made for the occasion. When visiting these monuments at cemeteries and battlegrounds, we would be given a certain narrative of the Second World War—of the importance of the anti-fascist resistance and the value of our country’s postwar project of “brotherhood and unity.'”

Miljački has mixed feelings about her experience. “That indoctrination was not always pleasant, but it certainly worked upon me in some way. There was a degree of preparation that involved sidestepping daily reality—a gradual transformation would occur as we were taken out of busy urban life and school, often to somewhere much more quiet and remote, moving from one world to another.”

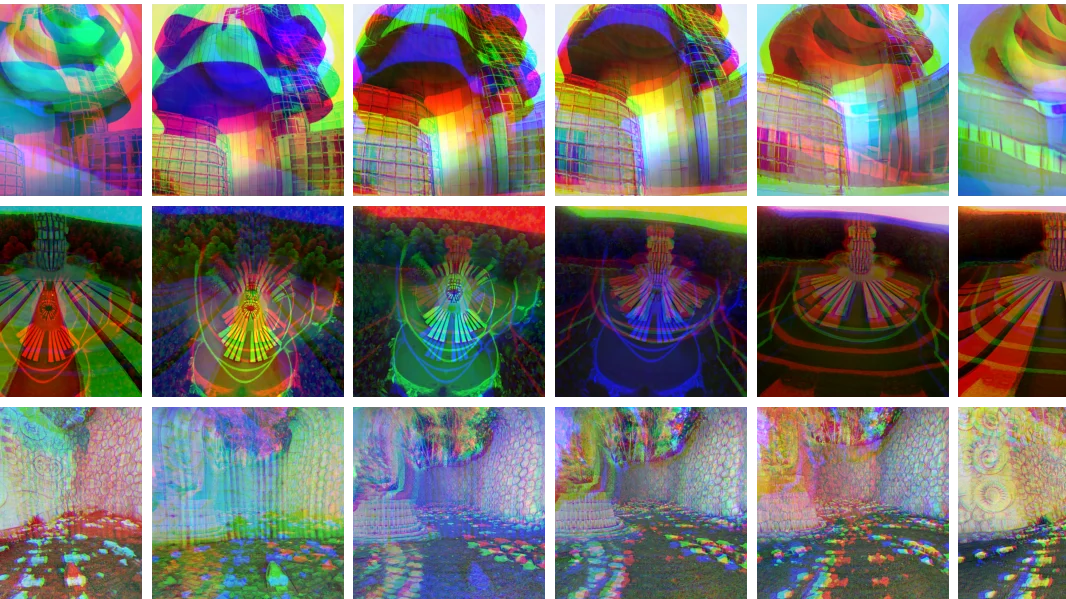

Those sites have since become icons of architectural tourism, representative of the ideals and expressions of Yugloslavia’s so-called “concrete utopia.” Social media photos are among those included in the data set, in addition to archival material and imagery from scholarly collections. “We specifically selected images that would enable us to produce the effect of slow motion around the monuments,” said Miljački. “The AI interpolates the images, filling out the ‘gaps’ between them to synthetically reproduce the atmosphere of an on-site visit.” The structures seem to pulse and breathe, an irresistible invitation to align our own rhythms and become part of the place seen on screen. An ambient soundscape developed from documentary material accompanies the installation—songs, speeches, and on-site field recordings—and the hypnotic pace of the visit is intended to deepen the viewer’s attention and sense of personal investment.

Hackable Propaganda

The aesthetic of the AI videos—both alluring and eerie—has an in-built criticality. Bootleg Futures, the umbrella concept for The Pilgrimage, is a speculative and critical project exploring how emerging AI technologies might serve as a tool for architectural ideation and critical commentary.

“Having fed our private and collective data to corporations, having turned history into databases devoured by predictive algorithms, many of the ways in which we engage, imagine, and shape the built environment are now predictable by AI technologies,” said Miljački. “But what if we tweaked, hacked, and strategically added new data into the stream of conversations about architecture?”

The videos are characterized by what Miljački describes as an “aesthetic of yearning”—appropriate for a medium that is inherently nostalgic, given that its predictive modeling is based upon data produced in the past. By generating virtual visits from past records of physical presence, The Pilgrimage invites visitors to contend with the human susceptibility for nostalgia—a feeling that can be critiqued even as it is cherished, prompting richer questions about what was desirable in the past and what can be gained for the future.

“As I see it, the best outcome of the project would be for people to become interested in the narratives behind these monuments, including the narrative and ideals of a country that no longer exists. Visitors will be given paper maps of Yugoslavia, marked with the locations of the monuments and a description of the project. It’s a way of communicating the concept and opening up conversation—but I also just like the idea of people walking around Venice with the map of that ghost country in their pockets. That’s very much part of it, for me.”

The map does not have an overt or authoritative message. It is simply present, until discarded. Likewise, Miljački maintains a degree of ambivalence in her attitude to the exhibition format itself—a broadcasting platform that can bewitch us with spectacle, or equip us with new tools for critical thinking. By treading the fine line between art and propaganda, The Pilgrimage challenges viewers to tell the difference.

Monuments included in The Pilgrimage

Interrupted Flight, Memorial Park Šumarice, Kragujevac, Serbia, Miodrag Živković, 1963.

The Battle of Sutjeska Memorial Monument in the Valley of Heroes in Tjentište, Bosnia and Herzegovina, by Miodrag Živković with Ranko Radović, 1971.

Stone Flower, Jasenovac, Croatia, Bogdan Bogdanović, 1966.

Monument to the Revolution on Kozara, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Dušan Džamonja with Marijana Hanzenković, 1972.

Partisan Memorial Cemetery in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bogdan Bogdanović, 1965.

Monument to the Uprising of the People of Kordun and Banija on Petrova Gora, Croatia, Vojin Bakić with Zoran Bakić, 1981.

Written by Matilda Bathurst

Editorial direction by Leah Talatinian