Language is the defining trait of being human, yet a deep knowledge of how it works did not develop until the 20th century. Pioneering linguists like Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle, MIT Institute Professors emeriti, were instrumental in the development of the field of modern linguistics. Since the 1960s, students have been drawn to the department to study the complexity and elegance of language through the lens of generative grammar. Sarah Hulsey, PhD ’08, is no exception, but her investigations of language have taken a different route since leaving MIT.

Hulsey earned a PhD in Linguistics from MIT, with Danny Fox as her dissertation advisor. Her research focus was syntax (the study of the structure of phrases and sentences in various languages) and semantics (the study of meaning). “The study of syntax and semantics together is a way of trying to understand how speakers build meaning out of the component parts—words,” says Hulsey. Now Hulsey thinks about the structure of language in the visual domain, using her background in linguistics to inform artist books and prints.

After finishing her doctorate and teaching linguistics for four years at Northeastern University, Hulsey decided to pursue art professionally. Printmaking and letterpress had captured her imagination while she was an undergraduate studying linguistics at Harvard University. There, Hulsey learned letterpress at Bow & Arrow Press and worked part-time in the print department at the Fogg Art Museum. “I was helping in the study room and I was able to see lots of prints and artist books by well-known artists I had read about in high school,” she recalls. “I became interested in printmaking through that experience.” A traveling fellowship took her to Europe in 2001-02 to study artist books. She found a studio and acquired a press during graduate school. Gradually, she recognized, “as much as I loved teaching and researching linguistics, outside of my job, I was spending most of my time at the studio, so I decided I wanted to study art formally.” She earned an MFA in Printmaking and Book Arts at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.

Through her art practice, she “discovered a way to make artwork that is about language.” She says, “When I started making art, I thought it was separate from my interest in language. But as I became drawn more towards printmaking, I realized unexpectedly that it shares certain attributes with language in that it is iterative where language is recursive; I realized that my interests in the two essentially came from the same place. Even though I am a professional artist today, I read linguistics papers and books and think about many of the same things I thought about at MIT—but express them in a very different way.”

CAST spoke with Hulsey in her studio in Somerville, MA, about her process, her residency at Mokuhanga Innovation Laboratory (MI-LAB) and her artist books acquired by the Rotch Library at MIT.

A CONVERSATION WITH SARAH HULSEY

For your artist books and woodblock prints, you often borrow imagery from scientific diagrams—from astronomy, geology, cartography or chemistry—in order to comment on some aspect of language. You also draw parallels between how letterpress printing is comprised of individual pieces of type and how language is made up of component parts. What is an example of a work that conveys some of these key ideas?

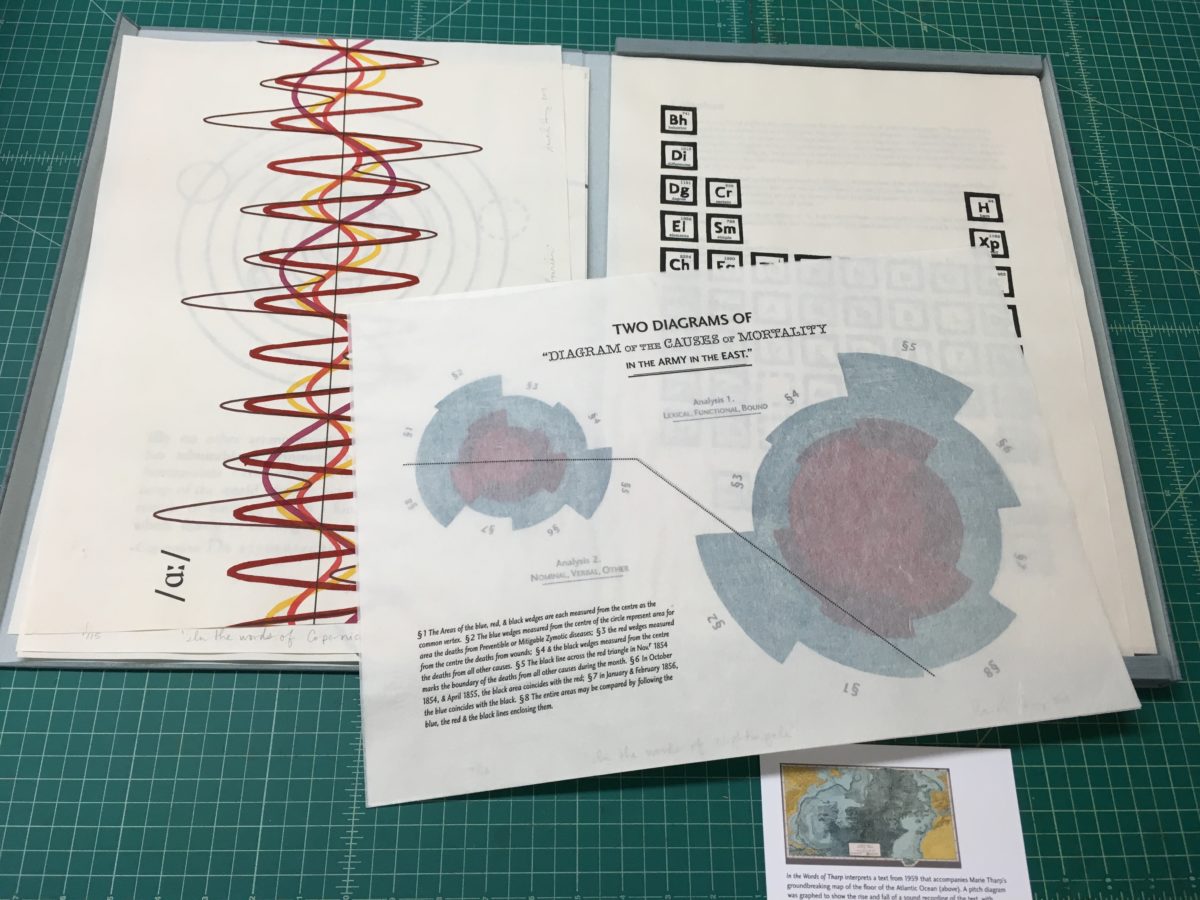

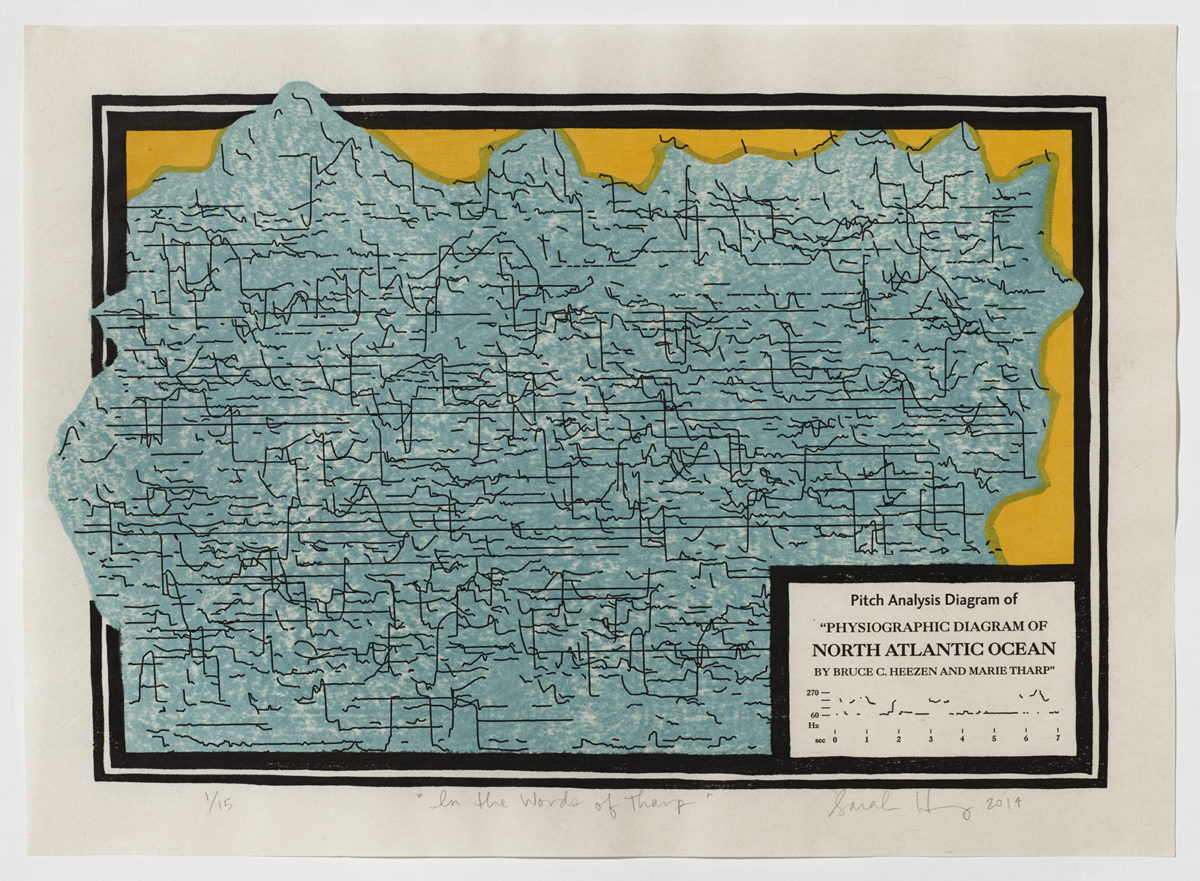

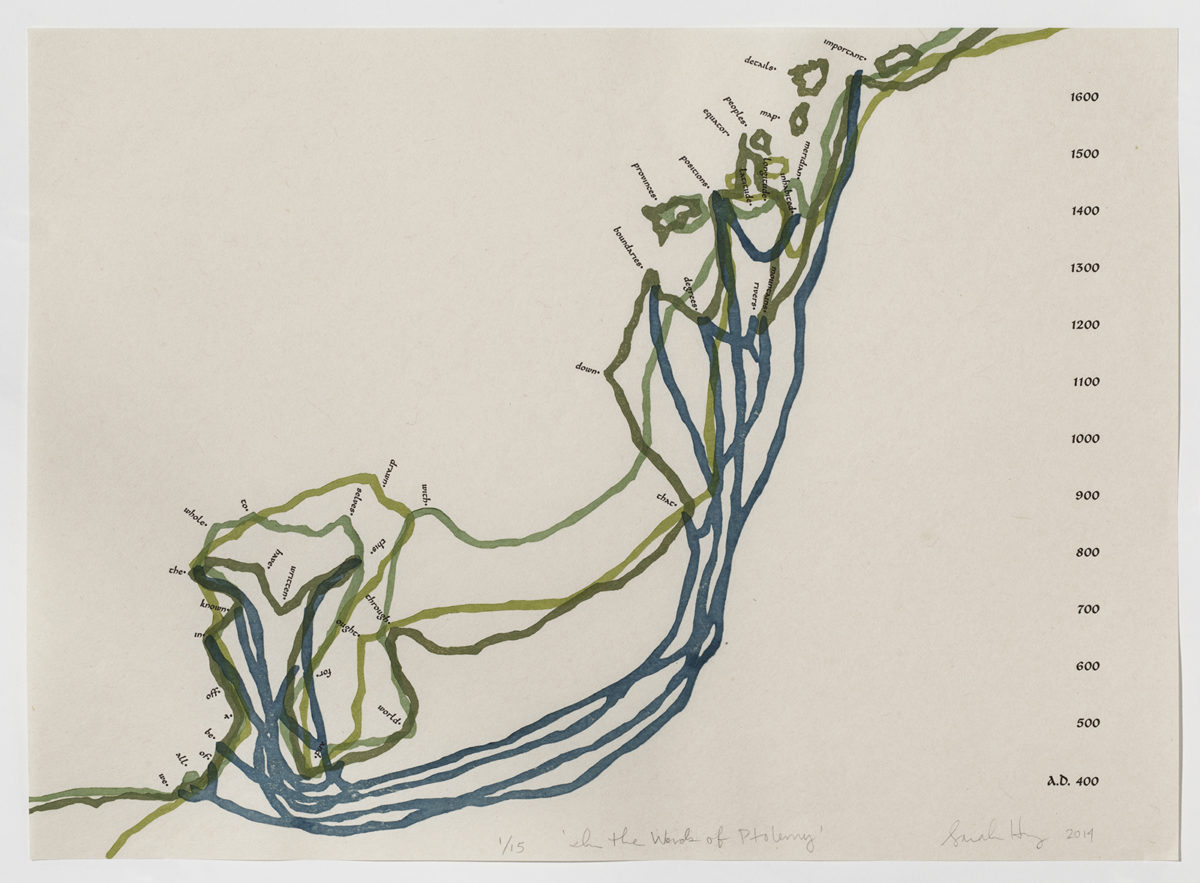

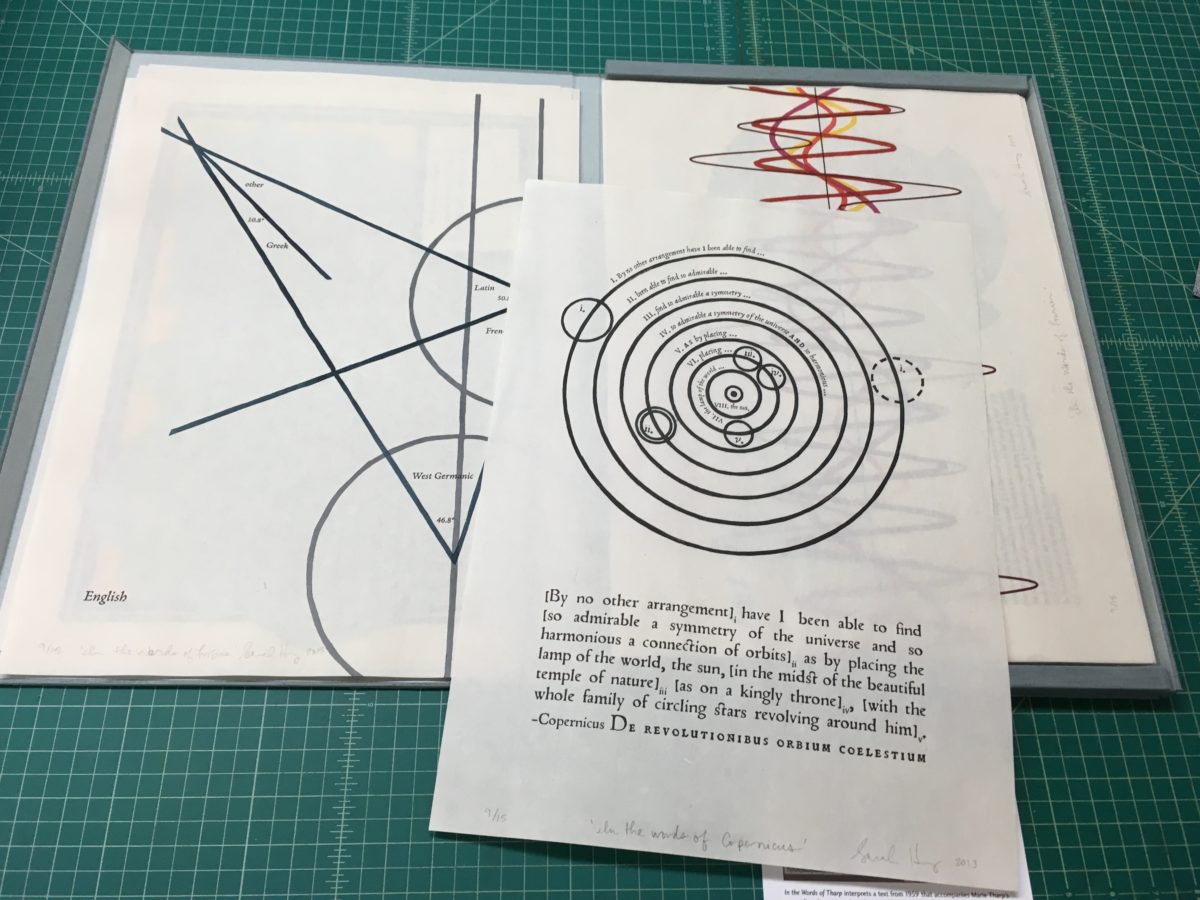

Diagraphia (2013-15) is a portfolio of prints that captures these ideas. For this project I took eight historical diagrams—some well known, like the Periodic Table, and some less well known. I chose images with a visual structure or complexity that could be reworked to reflect something about language. The diagrams vary in terms of subject, date and country of origin, but I chose them because they each had something that was analogous to some aspect of language.

For the first one, I used the heliocentric diagram of the solar system by Copernicus to reflect the hierarchy of phrases in a short passage that Copernicus wrote about his diagram. The result is a woodcut print that uses the same general format as the solar system diagram to instead represent something about the syntax of a text.

In each piece, there is some letterpress component. Some have the full text that I diagrammed. And they vary in terms of what area of language I’m representing. So, some refer to sentence structure, others to sound patterns or word distributions in a language.

I think it helps to have multiple images getting at similar ideas, so that over the course of looking at a portfolio, or a book or a suite of prints, the viewer starts to see patterns. And hopefully, some of those patterns will suggest language.

MIT Rotch Library purchased the last copy of this piece for their Limited Access Collection, along with my book, Asterisms (2017). It means a lot to me to have my work in the Art & Architecture library because MIT was so important in my education and in my thinking about language, which is foundational to how I think about my visual art work.

You were at a printmaking residency at Mokuhanga Innovation Laboratory (MI-LAB) in Japan. What is mokuhanga, and what is the residency like?

Mokuhanga is the Japanese word for woodblock printing. It varies from European woodblock printmaking, which is mostly oil based. The Japanese process uses watercolors. It’s the process developed in the Edo period (1615-1868) to create prints that were made in large editions. A lot of the Japanese prints we’re familiar with, like Hokusai’s prints of the Great Wave or Mount Fuji, are done in this process.

For Diagraphia, I used this process in conjunction with letterpress. It’s a nice process because you don’t need a printing press to do it. It is printed by hand. Because it uses hand ground pigments or watercolor, it doesn’t sit on the surface of the paper in the same way as oil based ink does. It almost has the effect of dying the paper. It’s more integrated into the luminous Japanese paper, and I think the organic quality of the printing is useful to suggest the biological, cognitive system of language.

I was at MI-LAB for five weeks doing the advanced mokuhanga residency with four other residents. It’s near Mount Fuji and the program began over 20 years ago to train non-Japanese artists in this form of printmaking. It gives artists the opportunity to learn from master printers, who advise you on the projects you propose.

What did you work on there?

In terms of technique, I wanted to work on how to print large. In mokuhanga, you carve one or more woodblocks, apply ink with a brush, lay the dampened paper on top of it, and print by hand using a tool called a baren, which is a flat disk covered in bamboo, to apply pressure. The paper and the block are dampened, and the technique works particularly well in Japan where it is humid. Because the paper is damp and you are using water-based inks, it doesn’t require the same amount of pressure as oil-based inks. In order to manipulate large-scale prints by hand, you have to be careful about the registration to ensure you get the sheet laid on each block correctly.

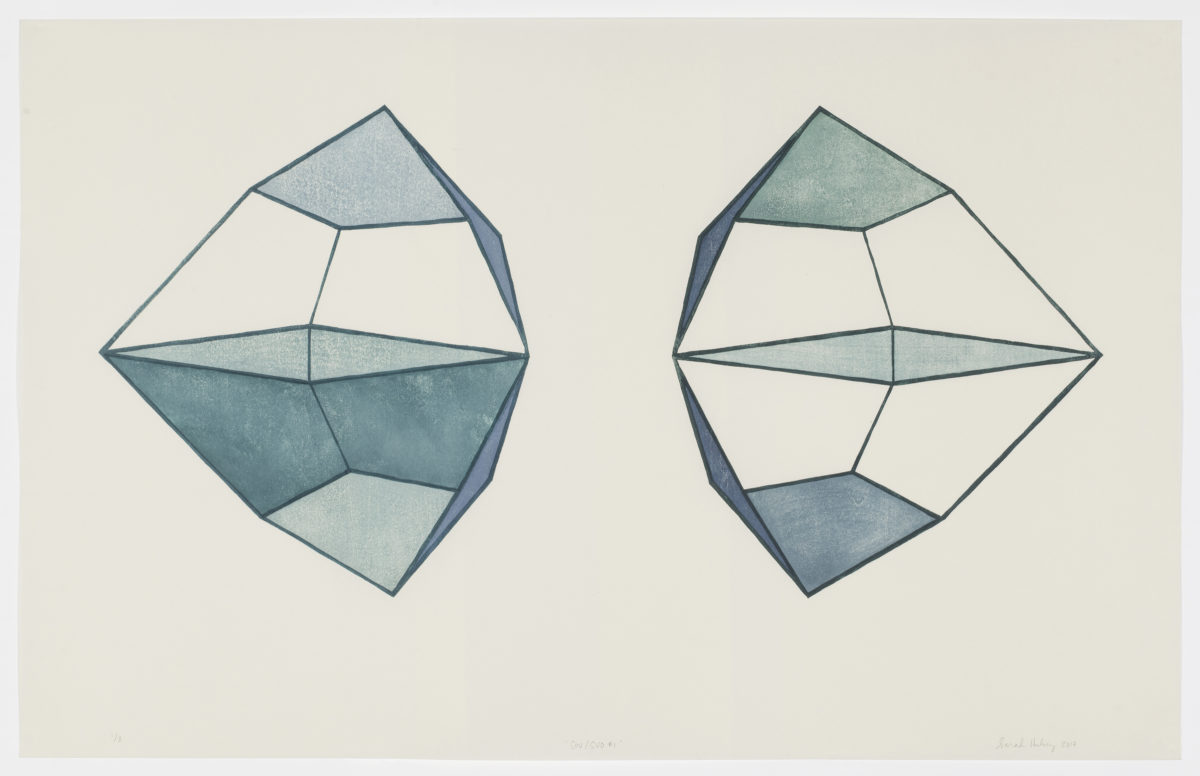

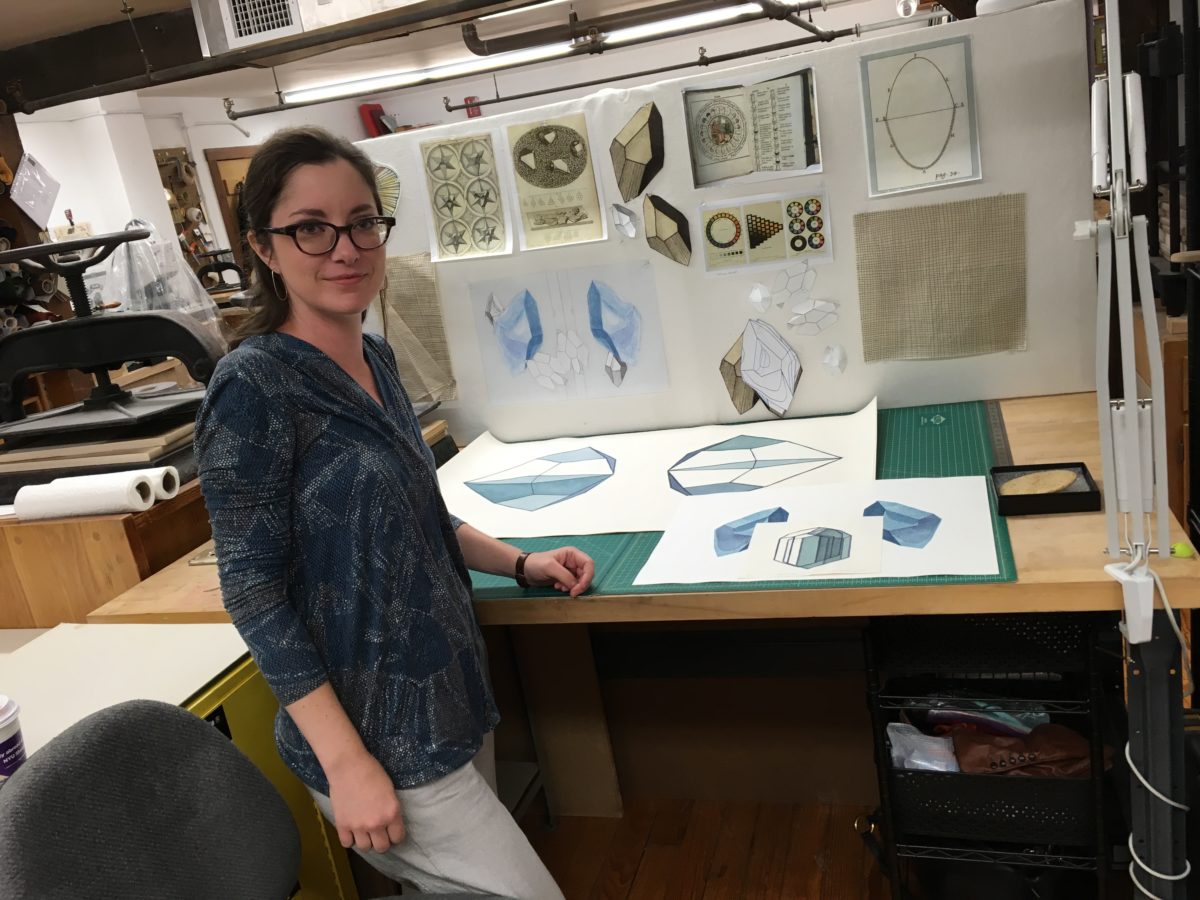

I did a series of four prints. The source material for the project was a late-eighteenth century book on geology, on crystal formations. It is a theoretical work that shows what were thought to be all the possible variations on crystalline shapes. I found all the facets visually beautiful, and some of the images are shown with their mirror image version. I used these images to think about how word order in certain pairs of languages can appear to be reversed relative to each other, or at least parts of it are reversed. In English and Japanese, for example, there are many phrases that look like they have opposite word orders to each other. The series, Stereosyntax, explores ways in which languages vary and things that are constant across all languages, which is one of the core questions of the field of linguistics.

You talk about in your essay, “Visual Reconstructions of Language” that for a decade you felt you were on two separate, unrelated tracks in your life, with linguistics and art. As someone who figured out how to merge your interests, do you have any advice for MIT students who may feel similarly?

I don’t think you can force it. It took me some time to realize, but I believe that my interest in language and my interest in art come from the same place. They both arise from a deep interest in how the mind processes the complex relationships within the domain of language. But if I had tried to force a connection earlier, I don’t think that some of the deeper connections would have been apparent to me. For me, at least, merging my two interests required pursuing each area independently before the commonalities began to emerge and I realized that my visual work was becoming a reflection of my thoughts on the structure of language.