Professor Emerita Joan Jonas taught at MIT from 1998–2014, and her pioneering performance, video, and installation works from 1960 onward have secured her a place in art history’s firmament. Influence, however, is a more personal and earthly matter; it occurs in the minds and studios of working artists, from workaday problem-solving to the heights of inspiration and everything in between.

To comprehend more fully Jonas’s extraordinary impact ahead of her work for the 2015 Venice Biennale’s US Pavilion, we asked several of her former MIT students and colleagues to share lessons she imparted that made an enduring impression on their artistic work. Jonas’s approach to her class, as these alumni recall, was characterized by openness, boundless curiosity, and vigorous exploration. In this interview series, Pia Lindman, Grady Gerbracht, Sohin Hwang, Rebecca Uchill and Sung Hwan Kim trace the lines of influence from their own art practices to the inimitable work of Joan Jonas.

REBECCA UCHILL

Rebecca Uchill received her PhD in 2015 from MIT in the Department of Architecture’s History, Theory and Criticism of Art and Architecture. She is an independent curator and Postdoctoral Associate in the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST). Her work focuses on the institutional conditions for art production, display, and dissemination. Her dissertation research on Alexander Dorner’s viewer experiences received fellowship support from the Social Science Research Council, the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, and the New England Society of Architectural Historians. In 2014–15, Uchill was a fellow at the Berlin Program for Advanced German and European Studies.

Tell us about your experiences in Jonas’s course 4.360, “Performance-Action (An Archaeology of the Sea)”

In the fall of 2008, at the start of my first semester as a student at MIT, I registered for Joan Jonas’s “Performance-Action (An Archaeology of the Sea).” I was incredibly excited about the course, and especially thrilled to meet Joan. I had first encountered her work as an undergrad nearly ten years prior, and her legacy as an artist across various media figured prominently in my thinking in the time since.

In the years immediately before beginning my PhD in MIT’s program in History, Theory and Criticism of Art, I worked as a curator at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, where I found myself becoming a kind of an activist for dematerialized art practices—art that was not beholden to one original observable material state, such as event-durational artwork or research-based art practices. This led me to become particularly interested in performance art as an object of museum administration. At the time, major institutional collaborations aimed to research and conjecture systems for the documenting (registration) and collecting (conservation) of performance as one of the more complex forms of time-based media. Joan’s work struck me as especially considered in its folding in the procedures of platform shift (deploying work created in one medium in another medium) as an artistic marker of temporal shift. Her performances and works using “live” technology were presented in video recordings that were not documents, but new video and installation artworks themselves. For example, her Vertical Roll (1972), originally utilizing the analogue television signal disruption of the same name as a kind of visual metronome, was later seen on digital television monitors that do not inherently produce the “roll.” Transitioning a live event or an obsolescent technology into an updated format was not a problem, but rather a core attribute of her art form. Allusions to/incorporations of prior works took on new meanings in updated contexts and formats.

I could not believe my great luck in being able to join Joan’s class. Upon enrolling, I proposed to write a paper on contemporary performance art exhibition history. About three weeks into the semester, Joan indicated her preference that I produce a work of art, like the other students in the course. My personal history of art production was comedic at best, and I was terrified by this instruction, but Joan offered to be a mentor throughout the process.

Overall, the class was an exercise in curiosity and experimentation, with the deep sea thematic as a touchstone. In one course meeting, Joan read aloud from Moby Dick while we moved through the room, open to embodied responses. We made a group field trip to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to learn more about their work. I borrowed a departmental video camera and spent a full day at the New England Aquarium filming jellyfish as they tangled themselves into living abstract drawings in three dimensions.

Over the course of engagement with the class themes, I became interested the fact that deep-sea archaeology explores sites untenable for human visitation. Its methods imply a type of exploration that is necessarily mediated by machines and tools, and this process of exploration through mediation was one my performance attempted to take up. I won’t humiliate myself by describing my final project for the course in detail—let it suffice to say that it was a great challenge, and I became even more admiring of artists who fearlessly face the task of making work. Joan and the incredible cohort of art students in the course (Caitlin Berrigan, Matthew Mazzotta, Haseeb Ahmed, Jessica Wheelock, among others) were all generous and willing participants in and contributors to my final project.

After the course ended I continued to learn from Joan through seeing her artworks re-presented, re-mediated, and re-animated in multiple forms: from her Reading Dante performance, presented at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 2008 and channeled in video in the 2009 Venice Biennial exhibition in the Arsenale, to her Reanimation, presented in its first version in the “cube” classroom beneath the MIT List Center galleries, followed by a series of larger-scale performances including a 2012 version at Documenta in Kassel.

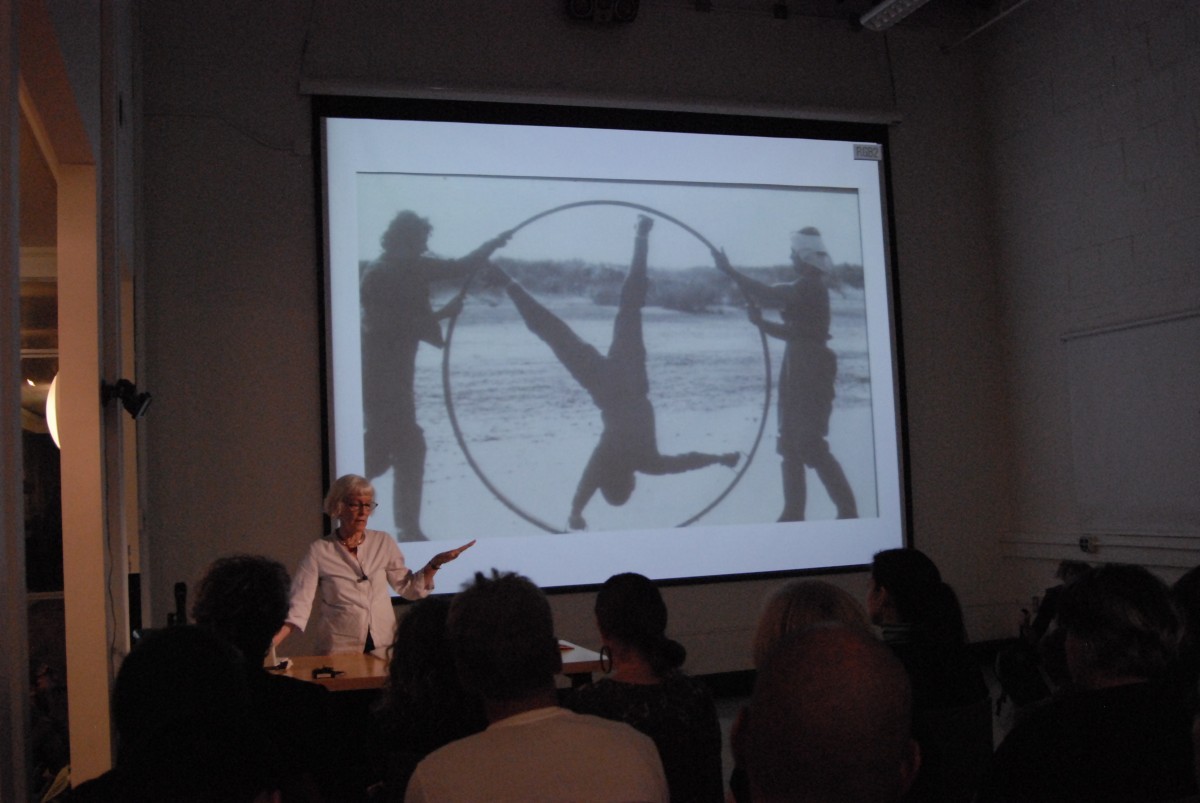

In 2010, I was invited to a discussion on performance art as part of a new departmental expansion at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. There, Joan spoke about her view that the original event of a performance could never be repeated the same way, and therefore a performance work could be translated into an exhibition format through other means. At the time, her work Mirage, originally conceived as a 1976 performance at Anthology Film Archives, was on view in a new installation format in MoMA’s galleries. It was a different work, in a completely different format, but it was carefully calibrated to invoke the memory and aesthetics of the original.

In seeing all of this developing work by Joan, I finally came to truly appreciate that the technologies that enable mediated exploration, or “remediation” of a past event, were not necessarily distancing apparatuses, as my bad performance for Joan’s course posited. Instead, Joan showed me how to embrace changes in time, place, and media as a kind of temporal, spatial and technological patina that add history, perspective and substance to a work.

Written by Rebecca Uchill, Arts at MIT